The original version of this essay was published in the Polycene Design Manual, an ongoing attempt to articulate a design standard in response to the polycrisis. It was created by the Center for Complexity at the Rhode Island School of Design, in collaboration with Horizon 2045 and the 10x100 network. This version contains some edits, corrections, and expansions. It is the first in a series titled Embodying Planetarity.

Click here to view a high-res visual map of this article, created by Mimi Shyngyssova.

How do we relate to the worlds—around, within, and beyond us? It is a simple question. Depending on how we answer it, we may end up with radically different ways of understanding and engaging with the planet. As we teeter on the edges of planetary collapse, it becomes urgent to recognize the implications of this relationality on how we frame our politics, our values and goals as a species, and our fundamental understanding of what it means to be human.

The metaphors we use shape the ethics we enact.

Consider Johannes Vermeer’s 1668 oil painting The Astronomer (fig. 1). A pensive white male looms over a man-made globe. His gaze lingers as he extends his hand to cup the curvature of the globe, insinuating the beginnings of a profound epiphany. What Vermeer presents here is a Cartesian relational ethic: the conscious astronomer examines a static globe in an attempt to understand the world it represents and ultimately transform it in his own image. In turn, it suggests notions of globalism, a world picture1 that frames the human-planet relationship as anthropic, inventing binary logics of natural/man-made, primitive/civilized, national/international, and local/global, among varying rationale for European colonization, ecological exploitation, and technocratic progress.

Now consider the Pale Blue Dot (fig. 2), a photograph of planet Earth taken by the Voyager I space probe at the suggestion of (another white astronomer) Carl Sagan2. Its subject: a tiny blue pixel, barely visible within the alternating bands of dust and light, and seemingly inconsequential until contextualized by Sagan’s well-known words, “That’s here. That’s Home. That’s us.” The Earth, a pale blue dot, “a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.” An iconic reminder of the fragile entanglement of life on Earth, that we’re all—quite literally—in this together. A delicate marble made of matter and energy, entangling the means of survival with its most intriguing product: life. As microbiologist Lynn Margulis put it:

No matter how much our own species preoccupies us, life is a far wider system. Life is an incredibly complex interdependence of matter and energy among millions of species beyond (and within) our own skin. These Earth aliens are our relatives, our ancestors, and part of us. They cycle our matter and bring us water and food. Without “the other” we do not survive.3

Embedded in this web of living and made-alive, the human condition is quite evidentially more-than-human.

This is the heart of planetarism—a political imaginary that makes our feedback loops with the Earth sustainable for us and for the extant order of life on Earth and in consideration of deep time and an expanding cosmic geography. This form of socio-ecological politics, Jeremy Bendik-Keymer notes, “does not continue the territorially fragmented sovereignty of the long shadow of European imperialism,”4 instead advocating for a relational ethic centered on epistemic humility and collective flourishing. Some key differences:

While globalism assumes a quantifiable representation of the world, one that both captures its essence and enables its manipulation, planetarism asserts that the Earth is more than its representation and requires a more responsible engagement with its complexity and diversity.

While globalism enables the reproduction of existing power inequalities, favoring certain groups over others, planetarism challenges these structures by foregrounding the fundamental inter/intra/extra-dependence of all life on Earth.

While globalism operates within a narrow temporal and spatial horizon, prioritizing short-term gains over long-term consequences, planetarism expands this by considering the past, present, and future of the Earth as well as its place within the larger cosmos.

Sitting with Uncertainty

The globe is on our computers. No one lives there.5

Even so, both globalism and planetarism are based on certain assumptions that may not adequately capture the reality of the world as it is. Both concepts rely on human-centric perspectives that often fail to account for the agency and autonomy of non-human entities. Tectonic plates shift, birds migrate, mycelial networks carry signals across forests. Ancient fossils slowly decompose into petroleum, pandemic-inducing pathogens lie dormant beneath the ice, even as unknown celestial objects plunge in and out of our solar system. The global and the planetary both imply a degree of coherence and stability that does not reflect the dynamic and unpredictable nature of the world, or the humans in it. In turn, both may obscure (or completely erase) the differences and conflicts that exist within and between various entities on Earth. It would appear that understanding the reality of the Earth requires an acknowledgement of the inherent impossibility of the task.

Gayatri Spivak makes a compelling case for this impossibility in her notion of planetarity, a fluctuating expression she uses to complicate our epistemic representations of the planet as being one unified field. To her, planetarity is a gesture of protest, a skeptical rejection of models that attempt to flatten all people, living beings, and ecosystems within a totalizing organizational logic (such as globe, world, international, or planet). It challenges the very idea of understanding the Earth, suggesting instead that our relationship with the planet be characterized by a critical unknowability. This highlights a crucial ingredient in our recipe for a new relationality: the ability to confront and sit with uncertainty.

Perhaps our relationship to the planet, in its complex entirety, must itself be made alive; our grounding ethic, then, be one of dynamic situatedness: rooted in a sense of wonder in the face of planetary unknowability but equally agile and responsive to the complexity of its evolving challenges.6 As we find ourselves at this crucial juncture in our shared history, where every day is an ALL-CAPS headline announcing yet another lethal calamity somewhere in the world, this negotiation of how we choose to relate to the world becomes crucial, especially if we are to ever build pathways towards mutual flourishing. So, we ask: how might we frame a relational ethic with the planet that responds respectfully and effectively to its ever-changing conditions and challenges? How do we—in practice—confront complexity? What does that look like?

These Bodies of Knowledge

We might start by drawing on the insights of feminist, indigenous, and postcolonial cosmologies, which have long questioned the dominant modes of knowledge production that have shaped our understanding of the world. These theories have illustrated the importance of situated knowledges7, relational ontologies8, and embodied practices9 as ways of engaging with the world in more nuanced and ethical ways. They emphasize the deep entanglement of how we see the world with where we see it from (and through), urging us to locate our production of knowledge in the physical bodies, social contexts, and ecological surroundings that inform them. In situating ourselves in the broad commonwealth of the more-than-human world, they challenge the edifice of human exceptionalism and the separation of our minds from our bodies, transforming Descartes’ proclamation of “I think therefore I am” into a grounded realization: “Here I am; therefore I think.”

To illustrate, we shift attention to our primate cousins, specifically to recurrent scientific efforts to locate evidence of their “intelligence.” Writing in Ways of Being. Animals, Plants, Machines: A Search for a Planetary Intelligence, James Bridle10 describes a common intelligence test that involves placing some tempting food just out of reach of an animal, and leaving them with a tool (like a stick or string) to obtain it. Most primates—apes, chimpanzees, gorillas, and others—will always make use of the instrument to snare the treat (either pulling the string or using the stick to drag it towards them). However, when the same test was conducted with a gibbon in 1932, it failed to pull the string on the floor, leaving scientists to conclude—by their very narrow definition—that it was “less intelligent” than other primates.

However, it wasn’t until a 1967 experiment with four other gibbons that this was formally disproved. The difference? Instead of leaving the string on the ground, researchers decided to hang it from the roof of the enclosure. The response was immediate: in one swift motion, the gibbon grasped at the hanging string, tugged it towards itself, and won not only the snack but also human approval of its intelligence. This new experiment was designed to account for the fact that gibbons are brachiators, meaning they use their arms to swing between the trees. As a result, their fingers are simply too elongated to pick up objects lying on flat surfaces, which means that their “intelligence” is built off of their relationship to their immediate environment: they reach for what’s above them. It wasn’t their intelligence that needed questioning but the cookie-cutter human model for assessing it.

As Bridle points out, the gibbons’ sense-perception functions in response to their specific biophysical relationship to their immediate world. Yet, too often, humans process the world in their own image. It’s no wonder that the Turing test—a popular method to test machine intelligence—was originally known as “the imitation game.” Quite literally, our measure for assessing a machine’s presence of mind was its ability to exhibit human-like behavior. In framing the non-human world—machine, primate, or otherwise—against a rigid anthropic model, we struggle to see what’s actually going on. As Bridle puts it, “Embodied as we are, with a different body pattern and pattern of awareness, we expect the solution to problems to match our own patterns.” These varied non-human body patterns may lie outside our perception, and yet, what we count (or don’t count) as intelligence is defined by the extent of human awareness. See where I’m going with this?

New Taxonomies of Relating

The gibbon example foregrounds two key insights: first, that relationality is a psychosomatic experience, in that an organism “does intelligence” through the interaction of its body with the world around it, and second, that perhaps the reality of the Earth lies somewhere within a broader gestalt of intersecting relational models.

Not only does humankind share the planet with an infinite number of matter-energy configurations (animals, plants, oceans, machines, and more), but also that each of these configurations has their own relational model with their world. Within this broader web of relationships, globalism’s human-centricity renders it deeply inadequate as a relational model. Similarly, while planetarism may account for some degree of these inter-relationships, it too fails in its inability to comprehensively confront the unknowable. In choosing how we relate to the world, how might we account for the limits of our sense-perceptions, especially given its intrinsic effect on what we count as intelligence, as knowledge, and as reality?

What we need, perhaps, are new taxonomies of relating. Language is a technology, in that it is “an active interface with the material world.”11 The question is if it’s enough in its current formulation, or if we require something dramatically different. For one, we have an obvious reliance on languages of imperial origin—-English mainly but also Spanish, French, and German, and in their standardized forms at that. As we shift our focus towards relational ethics, we inevitably confront the continuing influence of coloniality, conquest, and control on how we choose to understand and belong to this planet and to each other. The central provocation here is to realign this relationship with the planet, if we are to ever let go of the blinkered violence we have inherited from the continued legacy of globalism. We need to embrace the complexity, diversity, and unknowability of the planet as a source of strength and creativity rather than a problem to be solved or controlled, instead of forcing a Panopticon-like obsession with legibility and universalism. The planet is not a globe but a living macro-organism; a world where many worlds do and can fit, if we design and sustain systems to recognize and leverage its inherent intra-active pluralism. An evolved relational ethic may be key to our unfurling of an effective response-epoch, to navigate the uncertainties of our time and ensure the integrity of this pale blue dot that we are fortunate enough to call home.

Heidegger, M. (1977). The Age of the World Picture. Science and the Quest for Reality, 70–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-25249-7_3.

The original caption for ‘Pale Blue Dot’:

This narrow-angle color image of the Earth, dubbed ‘Pale Blue Dot’, is a part of the first ever ‘portrait’ of the solar system taken by Voyager 1. The spacecraft acquired a total of 60 frames for a mosaic of the solar system from a distance of more than 4 billion miles from Earth and about 32 degrees above the ecliptic. From Voyager's great distance Earth is a mere point of light, less than the size of a picture element even in the narrow-angle camera. Earth was a crescent only 0.12 pixel in size. Coincidentally, Earth lies right in the center of one of the scattered light rays resulting from taking the image so close to the sun. This blown-up image of the Earth was taken through three color filters – violet, blue and green – and recombined to produce the color image. The background features in the image are artifacts resulting from the magnification.

Margulis, L. (2013). In The Symbiotic Planet: A New Look at Evolution (p. 112). Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Bendik-Keymer, J. (2020, May 27). “Planetarity,” “Planetarism,” and the Interpersonal. e-flux. https://www.e-flux.com/notes/434304/planetarity-planetarism-and-the-interpersonal.

Spivak, G. C. (2015). ‘Planetarity’ (Box 4, Welt). Paragraph, 38(2), 290–292. https://doi.org/10.3366/para.2015.0166.

Zylinska, J. (2022, August). Performing Planetarity as a Method of Responsible Artistic Research. Miejsce (Place). https://www.doi.org/10.48285/ASPWAW.29564158.MCE.2022.8.3.

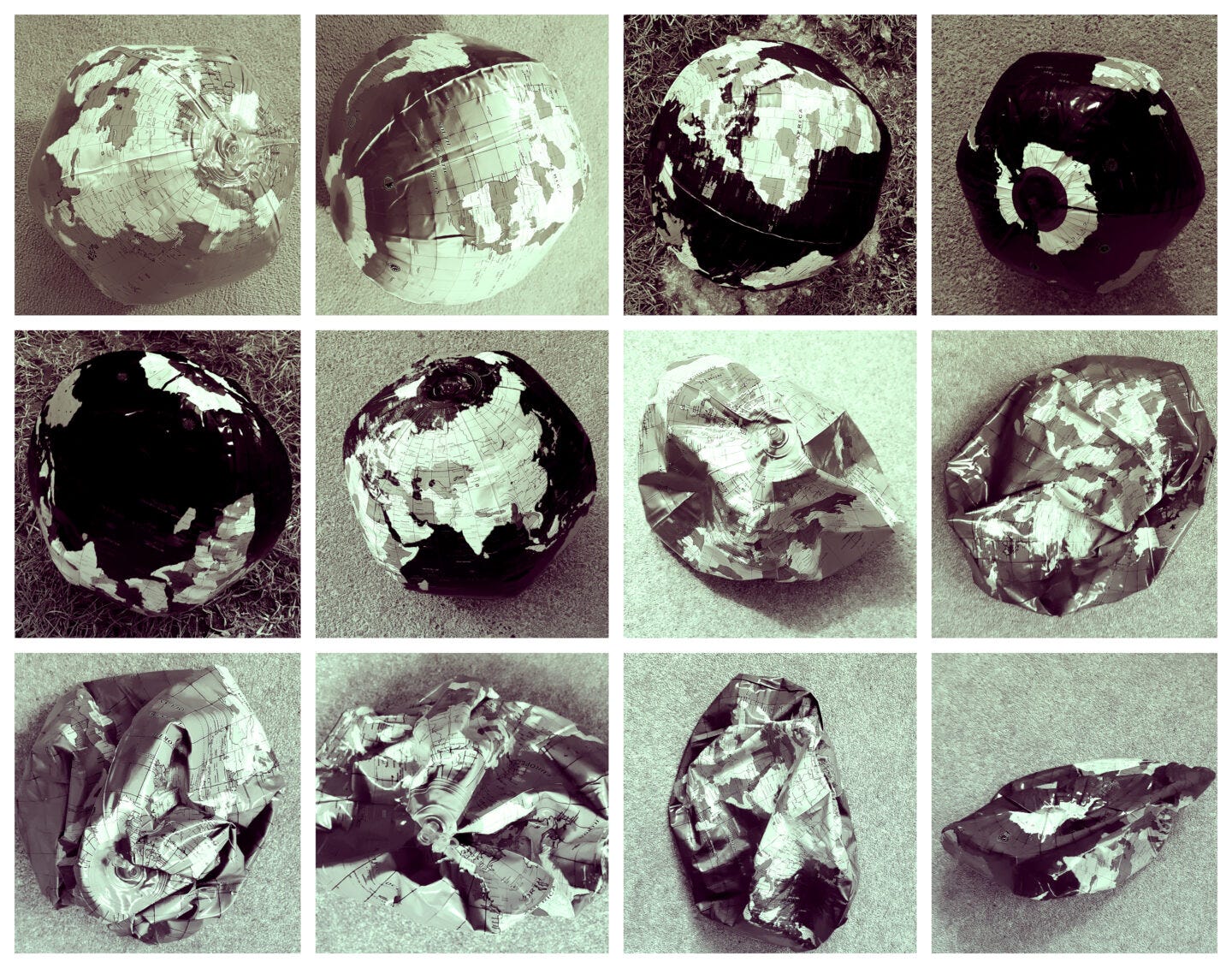

Zylinska, J. (2023). “Loser Images” for a Planetary Micro-Vision. In The Perception Machine: Our Photographic Future between the Eye and AI (pp. 167–192). Essay, MIT Press.

Situated knowledge refers to a feminist epistemological idea introduced by Donna Haraway, emphasizing that knowledge is always produced from a specific location and perspective, challenging the notion of objective, universal truths. It underscores the importance of recognizing and valuing diverse viewpoints, particularly those marginalized in traditional scientific discourse.

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066.

The term relational ontologies refer to the interconnectedness and interdependencies of entities, challenging traditional separations and distinctions. It emphasizes the idea that entities do not pre-exist but rather emerge through intra-actions, highlighting the entangled nature of reality.

Barad, Karen (2007). Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Duke University Press. Polkinghorne, J. C. (2010).

An embodied practice emphasizes the body's cultural and historical significance, challenging the traditional interpretations of the corporeal, and highlighting the deeply embedded role of the body in engendering autonomy and framing societal power dynamics.

Davis, K. (1997). Embodied Practices Feminist Perspectives on the Body. SAGE Publications

The latter half of this essay borrows some of its thinking—including the gibbon example—from James Bridle’s most recent book. Highly recommended for a more nuanced reading of the issues outlined here, especially pertaining to questions on intelligence.

Bridle, J. (2023). Ways of Being. Animals, Plants, Machines: The Search for a Planetary Intelligence. Penguin Books.

e-flux conversations. (2016, July 5). Ursula K. Le Guin: A rant about “technology.” https://conversations.e-flux.com/t/ursula-k-le-guin-a-rant-about-technology/3977.