This essay is the first in a series titled Notes on Trauma & Transition, and was written in collaboration with Lilly Manycolors, Justin W. Cook, Tim Maly, Martine Jarlgaard, Anum Naseer, among other colleagues at Center for Complexity and the Global Arts & Cultures department at the Rhode Island School of Design.

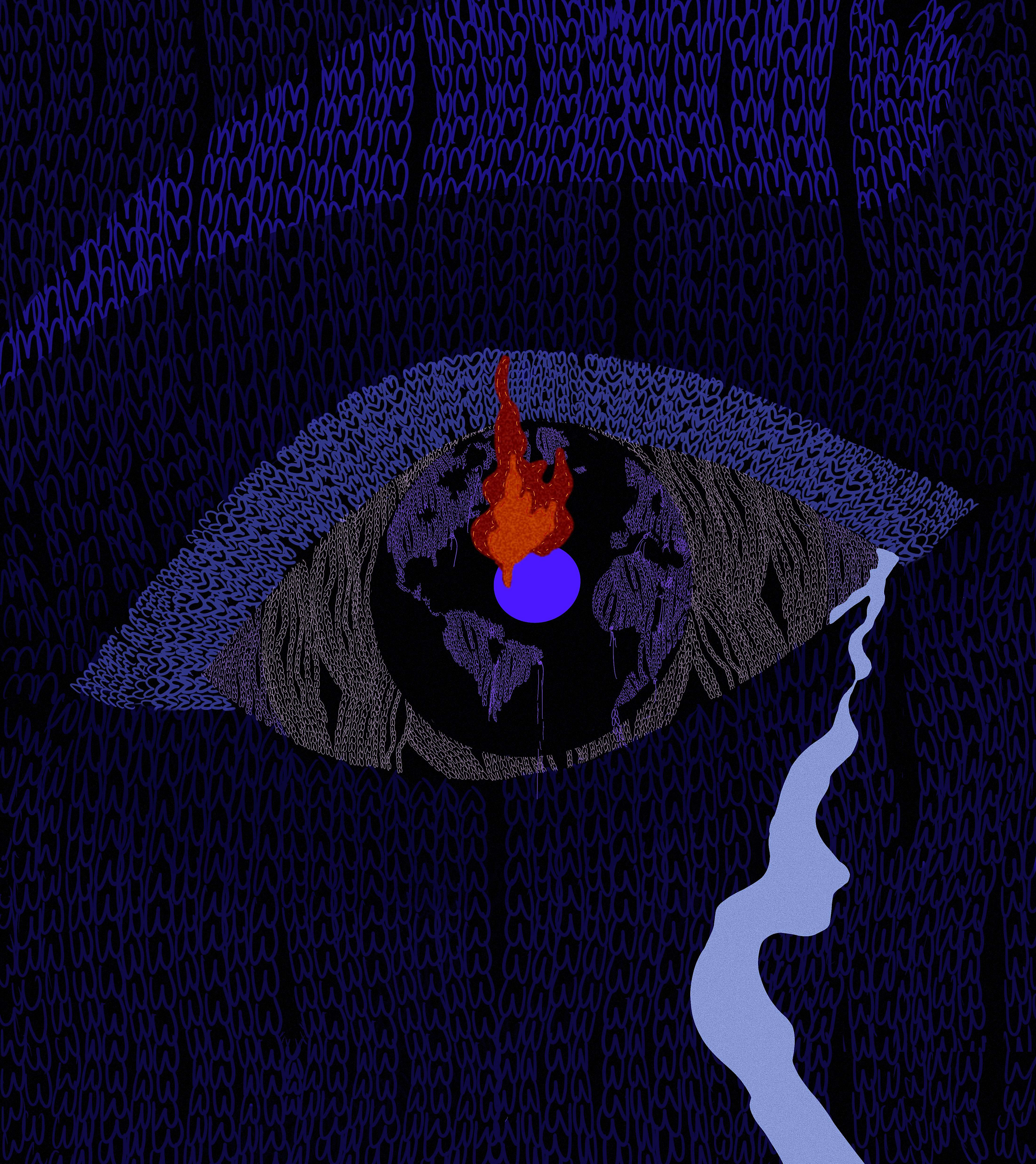

The Cry of the Beholder

There's a stark absurdity to the moment we find ourselves in.

Never before have we collectively experienced the making of history, with all its violent, volatile, and unequal contradictions, unfold in real-time. Armed with our screens, we devour everything—from extreme weather and climate collapse to racially-driven police brutality and genocide, each accompanied by a barrage of contradictory narratives, counter arguments, absurd humour, and outright trolling. By now, it’s common knowledge that this information overload leaves us profoundly overwhelmed, in a state of perpetual hypervigilant digital fatigue, and uniquely diminished under increasing bouts of grief, horror, and helplessness. When coupled with a growing pile-up of planetary crises—climate change, global pandemics, social inequality, cultural erosion, the rise of authoritarianism, et al.—this intricate nexus of emotions takes on a unique character that we term planetary melancholia. This is a thought experiment—to try and situate the personal within the planetary; and to make sense of what UN Secretary-General António Guterres has described as “an era of global burning”.1 How do we understand emotional dysregulation caused by the polycrisis—when the whole of our global challenges is far more dangerous than the sum of its parts. We find ourselves at a critical juncture, facing not just a climate crisis but a confluence of existential challenges.

In 2024, these disorienting processes have taken on an unprecedented scale, as unapologetic anti-planetary forces—ethno-fascist cults of personality, sectarian politics, racial othering, technocratic oligarchy, transhumanism, systematic climate denial, frontier warmongering, authoritarianism, and now full-blown genocidal megalomania—work overtime to co-opt mainstream media channels and violently defend and/or expand indentured structures of power. Irrespective of where one might lie on the political spectrum, our feeds simultaneously rearrange themselves into a curated pastiche of narratives that resist, co-opt, or celebrate these violent forces—depending on the individuated structure of our insular echo chambers (digital or otherwise) and the ideological centres we are most proximate to. As a result, the zeitgeist of today has become schizophrenic, alienating, and remarkably discontinuous.2

Steve Bannon, former head of far-right media outfit Brietbart reportedly said in 2018, “The Democrats don’t matter. The real opposition is the media. And the way to deal with them is to flood the zone with shit.” We see similar strategies used by a concerning number of populist, far-right and/or authoritarian governments worldover, such as in India, Argentina, and Germany, where the political and oligarchic apparatus leverage these overwhelming psychological experiences to manipulate public opinion.3 In fact, the same can be said for reactive elements on the left, although their interventions still base themselves on some modicum of civic reasonability. For instance—climate activists have taken to dousing iconic paintings in liquids, not out of disdain for art, but as a desperate plea for environmental awareness. Most recently, the group Just Stop Oil threw soup at Van Gogh's "Sunflowers" in the National Gallery, London. Ultimately, in an attention economy, spectacle is currency. But it is also a reflection of the complex emotional landscape we navigate, submerged in potent expressions of collective grief, anger, and uncertainty.

None of this is new knowledge; neither is this just a digital phenomenon or only limited to humanity. Rushkoff calls this 'present shock' (a contemporary analysis of Toffter's notion of ‘future shock’)4; others have pontificated extensively on post-truth politics, digital tribalism, and the erosion of public discourse.5 These conceptual framings were useful in the 2010s when technological and economic growth first began exploding at dramatically unprecedented rates. However, they fail to offer a comprehensive analysis of the emotional and psychosocial pathologies that are unique to this schizophrenic millennium; pathologies that must be understood and negotiated equitably if we are to make a meaningful and sustainable transition to a system of mutual thriving.6

Climate Anxiety Is An Inadequate Term

More recently, scholars and climate activists have offered terms like 'climate anxiety’ and ‘eco-grief' to refer to the psychological distress of witnessing our biosphere crumble before our eyes. Pihkala, P., writing in Eco-anxiety and Environmental Education, discusses how these notions bring us somewhat closer to a contemporary understanding of the issue given their ability to situate the personal within the planetary, and acknowledging that the psychological and spiritual challenges of this moment are not limited to the human experience.7 Unfortunately, these terms are still inadequate when confronted by the intersectional nature of the polycrisis and the inherent relationality of multi-species psychology, sociality, power, privilege, and personhood.

Writing in Clinical Psychology Forum, Barnwell, et al. argue that “‘climate anxiety’ cannot speak to the myriad social & environmental justice issues that shape psychological distress in the global south.”8 Using South Africa as an example—where mines are often placed in majority Black communities—they describe how psychological distress is connected to underlying asymmetrical power relationships that climate change is now making worse. In a similar vein, Sarah Jaquette Ray points out that climate anxiety is “an overwhelmingly White phenomenon”9. Ashlee Cunsolo’s research in the circumpolar north of Canada demonstrates this here:

She’s documented the ecological grief that many Inuit people in Labrador feel as they witness the ice—a vital part of their identity—vanishing before their eyes, and how it is so much more than just grief. It is the emotional impact of experiencing colonization all over again as their traditions melt away because of a crisis that they had nothing to do with creating.10

Terms like ‘climate anxiety’ or ‘eco-grief’ conflate the material experiences of those most at risk with the psychological distress of voyeuristic content consumption, in turn inventing an illusion of presence and proximity that obscures underlying disparities in vulnerability and impact.

On reading a draft of this article, scholar and artist Lilly Manycolors pointed out that these existing frames are shockingly abhorrent of the constant state of trauma and shock experienced by non-human species, despite their purported reference to the ‘climate’. Speaking to the concept of ‘phenological mismatch’, James Bridle explores the dissonance between the timing of ecological events and the expected patterns shaped by a stable climate, highlighting how climate change induces a misalignment in the natural world's rhythms.11 He points to growing instances of flowers blooming out of sync with their pollinators due to climate change-induced shifts, or migratory birds encountering dramatically different weather conditions on arrival, among various other examples of non-human expressions of dysregulation and stress. These instances of non-human species reacting and evolving from experiences with the Anthropocene in turn affects the human experience and response to these ongoing crises—most often in reaction to yet another catastrophic spectacle—inducing a cyclical cause and effect process that actively shapes macro and micro realities around the planet. Arguably, the release of pandemic-inducing pathogens, formerly trapped in millennia-old ice, could be read as a planetary expression of deep turmoil.

In this moment of deep planetary distress, we have engulfed ourselves in a tireless flood of hypervigilant virtue signalling, projection, and emotional dysregulation that often veils discursive and material nuance by creating the conditions that engender and nurture ideological polarities and anthropocentric denial. Ultimately, this cacophonic intra-active exchange of psychosocial pain is melancholia experienced at a planetary scale.

Melancholia in the Anthropocene

The psychological canon has often differentiated melancholia as being the internalisation of loss and an endless engagement with an “absent object”. Unlike the outward expression of an experienced loss through ‘mourning’, ‘melancholia’ as an enduring unresolved grief provides a critical lens through which to view the Anthropocene's more pervasive sense of loss. "The Future of Environmental Criticism" by Buell (2005) navigates the emotional terrain of ecological degradation, suggesting that melancholia manifests in the collective mourning for lost landscapes and disrupted ecosystems. Similarly, the concept of "solastalgia",12 a form of environmental melancholia experienced in the face of landscape transformation and climate change, further expands the dialogue within an ecological context.

Kristeva's "Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia" (1989) delves into the symbolic and linguistic dimensions of melancholia, offering insights into the articulation of sorrow and the role of creativity in navigating the abyss of despair. Her analysis underscores the profound existential inquiry at the heart of melancholia. Further, "Dark Ecology" by Morton (2016) and "Learning to Die in the Anthropocene" by Scranton (2015) both confront the philosophical and ethical implications of living in an era defined by human impact on the Earth. How does this emotional awareness get stored? Are there known methods for release? These works explore the intertwining of ecological crises with cultural and existential melancholia, advocating for a radical acceptance of our entanglement with nonhuman life and the planet's geological processes.

By weaving together these threads, we can discern a trajectory in the literature that mirrors the evolution of melancholia from a personal affliction to a collective, planetary condition, underlining the critical need to understand and address the complex emotional responses elicited by the current ecological and existential crises. Additionally, it reveals the systemic barriers that enforce ubiquitous survival mode, disallowing the time/space/resources to sublimate unresolved emotions. We term this condition planetary melancholia to capture the complex interplay of emotional reactivity, transgenerational trauma, ideological projection, moral injury, anthropocentric bias, and propagandised manipulation by state, religious, and/or corporate entities, allowing us to read these psychosocial experiences not as isolated events but as relational processes.

The Dimensions of Planetary Melancholia

01 Networked Emotionality: Connectivity and Its Discontents

As previously articulated—Emotionality in today’s planetary paradigm is inherently relational. Emotions are not isolated phenomena confined within individuals, but are deeply intertwined within our social and environmental contexts. Emotions are contagious, and have the capacity to spread and resonate within groups and communities. Shared emotions can foster a sense of collective identity, solidarity, and belonging. When we witness others expressing emotions, we often find ourselves experiencing similar feelings, engendering a powerful psychological resonance.

The interconnectedness of our emotions in the digital age, amplified by the rapid dissemination of (dis)information, primes us for a collective emotional experience that is both profound and incredibly overwhelming. This networked emotionality, while offering new avenues for solidarity, also exposes us to the vicissitudes of collective grief and existential angst, creating a landscape that is ripe for ideological manipulation and abuse. Tiktok, tiktok, times running out.

At the same time, expanding our epistemic frame to encompass the enormous mycorrhizal networks that allow trees to communicate and share nutrients, allows us to discover that this connectivity is inherent to the planetary condition. As biologist Merlin Sheldrake explains:

There wouldn’t be something called soil were it not for the action of decomposer fungi who disassemble organic material—like wood or the dead body of a fox—into simpler components, which then form part of what we think of as soil.13

Mycelium, in conjunction with a wide array of micro and macro planetary processes, inform the relationality at the centre of the polycrisis and in our framing of planetary melancholia.14 Here, Anderson:

We are living in transformative times; decomposition is everywhere. I have watched so many people make evolutionary leaps in their lives over the last few years. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that it has happened during a time when death has been so present, or that humanity’s fascination with fungi has flourished during that same time. Fungi remind us that life and death are not enemies, but friends. Death is what turns life’s wheel. What we see as a breaking down can be used for growth—or better yet, the genesis of something new.15

Anderson’s hope is inspiring but does not account for the unique experiences of evolutionary disadvantage embedded in our crisis-laden landscape.

02 Ambiguous Loss: A Catastrophe Without Event

We find ourselves navigating a sea of tumultuous emotions that defy traditional moorings of grief and mourning. This experience of loss is unique in that, "it does not hold a promise of anything like resolution." According to Pauline Boss, professor emeritus at the University of Minnesota, this is an ambiguous loss.16

Boss' insights into these ambiguous losses are a mirror to the polycrisis itself—a constellation of crises that elude definitive answers or outcomes. In a world where change outpaces our ability to process it, these ambiguous losses encapsulate the dissonance between our desire for closure and the reality of ongoing, unresolved change. How do you grieve when every day brings with it new reasons to mourn? If grief is a manifestation of change, how do you grieve with any semblance of integrity when change occurs faster than you can mourn it? Writing in “Waiting for the End: Narrating and Grieving Extinction”, Sarah France argues that the:

Refusal to accept the reality of ongoing climate change can partially be linked to the difficulty posed in acknowledging, articulating, and conceptualising climate change and its potentially devastating consequences. Eva Horn argues that this stems in part from climate change being a ‘catastrophe without event’ – a catastrophe that lacks a single geographical and temporal location, and that has global, long-lasting, and destructive consequences. [...]

This difficulty in identifying a clear origin, or even a clear outcome, is part of what contributes to climate change denial or skepticism, and it also contributes to the difficulty in forging a narrative around environmental catastrophe – a concern that Rob Nixon raises when considering the "slow violence" of climate change.

Pauline Boss explains how this ambiguity contributes to a growing sense of discomfort and unease:

We come from a culture [...] of, I think, mastery orientation. We like to solve problems. We’re not comfortable with unanswered questions, and this [the polycrisis] is full of unanswered questions. These are losses that are minus facts. Somebody’s gone. You don’t know where they are. You don’t know if they’re alive or dead. You don’t know if they’re coming back. That kind of mystery, I think, gives us a feeling of helplessness that we’re very uncomfortable with as a society.17

This aversion to uncertainty, to the unresolved discontinuities that the polycrisis perpetuates, leads us down a labyrinth of emotional and psychological complexities. The line between the individual and the collective experience of loss begins to blur, weaving a tapestry of grief that is both deeply personal and profoundly universal. How the hell are we supposed to deal?

[...] the only way to live with ambiguous loss is to hold two opposing ideas in your mind at the same time. [...] With the physically missing, people might say, ‘He’s gone, he’s probably dead, and maybe not,’ or ‘He may be coming back, but maybe not.’ Those kinds of thinking are common, and it is the only way that people can lower the stress of living with the ambiguity.

Boss clarifies, however, that these are not symptoms of a pathological psyche but a pathological situation. The situation is crazy, not you. In times where our traditional mechanisms of mourning—biological, social, and/or cultural—are either under attack from the alienating forces of neoliberalism, or unable to respond to the accelerating complexities of the polycrisis, we must begin considering alternative methodologies to unravel and make sense of our individual and collective grief.

03 Moral Injury: Ideological Rupture and the Challenge to Self-Integrity

The contemporary moment is ideologically disruptive. The visible rise of right-wing sentiments can be read as direct responses to planetary scale helplessness and climate change-induced energy/resource insecurity. As a result, we see nations becoming increasingly insular; geopolitically, we are moving from a (supposed) paradigm of globalisation and free trade to one that prioritises national interest.18 Further, the nature of right-wing conservatism engenders the active conflation of national security with the personal safety of individual citizens.

To reiterate, the settler insistence on violent racialization and frontier warmongering feeds into the rhetoric that the security of an individual citizen requires the security of the entire nation; by extension: the security of the nation requires the active defence against and management of extra-national entities and unpredictable externalities. Today, we are witnessing the most extreme and disturbing form of this rhetoric with the entire population of Gaza being held responsible for their supposed crimes against Israel and therefore, Israelis. But this rhetoric obscures the unimaginable damage inflicted by the Israelis in Gaza—by now, the heartbreaking numbers are common knowledge. What is somewhat less apparent is the profound cognitive dissonance required to inflict such terror in the first place—fueled by the conflation of individual fears in an era of overwhelming uncertainty and transgenerational pain with national and ethnic ambitions for land, mineral resources, and energy.

When faced with such vivid ruptures between ideological rhetoric and action on the ground, individuals increasingly report feeling a kind of ‘moral injury’. First used to describe soldiers’ responses to their actions in war, this "deep soul wound”19 is not just a personal crisis but a communal and biological one—pathological outcomes being PTSD or ‘shell shock’—reflecting a broader struggle with the implications of national actions that seem to betray foundational moral commitments. For Jewish people, this can mean wrestling with the complex legacy of survival and resilience against persecution, now juxtaposed against the actions of a state that purports to act for their security but at the cost of another people's freedom and dignity. Take the case of Dr. Alice Rothchild—Born into an Orthodox, Zionist family, she underwent a significant transformation in her views on the Israeli settler colonial project, going so far as to dedicate her life towards the Palestinian cause. She has since written multiple books on the issue; unsurprisingly, she has been wrongly deemed a “self-hating Jew” by reactionary Israeli agents for making statements such as the following:

I found that for many, publicly stating that Jews could be victimizers as well as victims, and that Palestinians are equally human and deeply hurting, is unthinkable and a betrayal of Jewish loyalty and identity. This Jewish denial combined with the increasing brutality of the Israeli occupation is made possible by keeping Palestinians invisible as fellow human beings.

Where are the protests from political organizations, the cries of horror from U.S. ministers as well as rabbis and mainstream Jewish community groups who cry “Never again!” Surely history will teach us that Israel cannot claim a special moral dispensation because of past suffering, and then behave immorally. Misusing the term anti-Semitism to characterize criticism of Israeli behavior ultimately renders the term meaningless.

Rothchild’s critique of the term “anti-Semitism”, as well as the intimidation she has experienced since, are both variegated manifestations of moral injury, among many many other examples.20 Such instances underscore the profound disquiet arising when our actions—or those undertaken on our behalf—clash with the ethical imperatives of our shared humanity. In the face of climate change, environmental degradation, and the resurgence of settler colonial violence, moral injury reflects the internal conflict experienced by individuals and communities as they navigate the contradictions between lived values and observed realities. It highlights a critical aspect of planetary melancholia: the grief not only for the planet but for the integrity of our moral landscapes, eroded by the very crises we seek to address.

04 Transgenerational Trauma: Ghosts in Our Bloodstream

Thinking of melancholia in planetary terms allows us to expand the geographic and temporal scales of our epistemic models.

Building on Paul Gilroy’s articulation of ‘postcolonial melancholia,’21 these complex emotions can be read as activators of transgenerational trauma and epigenetic memory. This illustrates how the climate crisis not only exacerbates the immediate environmental and social challenges but also reawakens the traumatic memories of colonial land loss, reanimating historic and generational tensions within global society. This reactivation of trauma underscores the profound and often underexplored ways in which historical injustices continue to shape the experiences and responses of communities to contemporary crises.

In 1979 psychologist Stuart Lieberman named ‘transgenerational grief’ to define “a loss and attendant grief experience [that] may so profoundly affect a family that it shifts their ways of being in ways fundamental enough as to move through generations of a family.”2223 He continues, “‘If family members are unable to mourn separately or collectively, a family pattern develops that may be transmitted transgenerationally.” In sociological terms, this family pattern creates a kind of ‘survival shape’, argues adrienne marie brown:

I think we have generations of people where it's like, oh, my parents are so tough, or my parents are so rigid or they're so disciplined, or there's other things. And I'm like, that's all grief too, right? And it's like the way that they process the grief is to become this exact thing. And I see it in my own family, where I'm like, oh, coming out of the conditions of black poverty, [...] there's a commitment to discipline in my family and to rigidity and order and doing things correctly and doing things according to the law and the rule. And I'm like, yeah. That's a survival shape [...] but it's also like, this is how you survive a place that doesn't want you to live.24

Reflecting on the generational shifts in these survival shapes, the landscape of emotional intelligence today has notably transformed. That prior generations displayed an overwhelming stoicism and resistance to emotionality reflects the religious and political cosmologies they grew up in. Building on brown’s stipulation above, so many people of the global majority have survived and are surviving varying extremes of poverty, social discrimination, and violence; not to mention growing up under the threat of nuclear war, among other Cold War-induced threats. Renee Lertzman, a psychologist with the Climate Psychology Alliance, shares her personal narrative of growing up during the era of nuclear fear, highlighting how this backdrop served as an early catalyst for her acute awareness of existential threats. Lertzman notes that she feels a similar sense of panic when thinking of the climate crisis. “There are really important parallels: The threats are human-created, and there’s a pervasive, visceral anxiety about the future at all times.”25

Yet much of Lertzman’s research has been into how the threat of climate collapse, with all its attendant dangers and adjacent challenges, is unique to our time. ‘Unlike the nuclear threat, we’re talking about how we live,’ she continues. How this is expressed in younger generations—especially Gen Z, Gen Alpha, and other overwhelmingly digital-first age groups—can tell us a lot about their developmental progress. Unfortunately, the younger ones have not had that luxury of going through earlier developmental stages without thinking about the climate crisis. Here, Britt Wray:

They are observing the lack of adequate action. This is reinforced by what they are seeing on social media and in talking with their friends. For some, that’s coming in before they have had a chance to figure out important aspects of their identity.26

As a result, and with growing access to critical and radical knowledge—anticolonial, BIPOC, feminist, disabled, queer, among other intersections—these younger generations are arguably leading our collective negotiation of today’s emotional landscape. Lennon Flowers, founder of the Dinner Party, a platform for people in their 20s, 30s and early 40s grieving the death of a loved one and seeking peers, community and a meal, had this to say:

Increasingly, vulnerability is in vogue. [..] There’s an emerging cultural currency for being able to say out loud the experiences that, in previous generations, we were asked to keep under lock and key.27

As we unpack the dimensions of planetary melancholia, perhaps we should turn to our younger and arguably more capable stewards for a way through these emotional and spiritual challenges, even as we begin to unpack the biological landscapes that play into them.

Bordering Biological Continuity

While there is strong “evidence” to suggest a correlation between the deep-rooted colonial trauma inflicted across generations and its molecular recording within the body, trauma itself remains purposely “untranslatable” within the Western imagination. Until we catch up to Indigenous scientific wisdom, the material remains to show us a recognizable trace, but is still being read and dismissed as “illegible,” in Western medicine. The cascade from emotional distress to pathological susceptibility has and remains a known pathway within traditional systems that once protected both community and environmental health. Susto (fright) is a common term first established in Nahua healing rituals, and is still implemented in modern day Nahua-Latino communities of the Sierra de Puebla in Mexico. Where, “theories of pathogenesis interweave with and adapt the old to the new,” susto is an, “indigenous idea that an "old" fright, one that has been forgotten and left untreated, may lead to a more serious illness.”28 The fright is nonspecific, but considered susto when negative somatic effects are bound up with “non-corporeal part of the person in a manner that can also be considered as a ‘falling away.’” 29

Where the once cosmic purview of life established an interrelated system between all beings, a new system founded on land ownership, individuality, and humancentric legibility has violently disrupted the equilibrium between inner/outer flows of vitality. Now, we find ourselves in an age of falsified innovation; texturizing what has already been felt with exclusionary evidential claims, that is remarkably agnostic of the intangible and the spiritual. As our colleague Lilly Manycolors often reminds us, “Mental illness is a spiritual injury.” Yet, post-Enlightenment obsessions with empirical predictability has trapped us within increasingly discontinuous epistemologies disguised by claims of objective rationality, measurement, and scientific progress.

Epigenetics—termed by embryologist Conrad Waddington in 1956—refers to the phenotypic differences accounted for by change in gene expression, rather than alteration of the genome itself. In other words, a transformation of the expression of a sentence, rather than the letters within it.

The infamous “epigenetic landscape” model that Waddington proposed in 1956, is one of the earliest Western scientific theories that complicated the linear machination of the central dogma.30 A turning point for scientists to undo the passive individualism reinforced within biology, a type of resistance to Descartes’ I think therefore I am logic.

The implicit purity of the central dogma denies a relativistic reading of the body, more in favour of linearity and direct realism.31 It purposefully excludes environmental factors so that genetic material can be regarded as a 1:1 reflection of the organism that it manifests—a Scarlet letter that the individual cannot escape.32

In Waddington’s 1957 illustration of a ball rolling down a hill, the embryologist and avid art enthusiast, communicates the complex journey delineating a cell’s identity, upended by various interactions between an exterior environment and a complex genetic milieu buried within the body (fig. 3).33 An adapted physiological response to environmental stressors, Waddington initially proposed that the flexible landscape could alter shape, preparing itself to respond more sharply in subsequent generations.

Whether the environment is captured through physical molecules (pollutants that are inhaled or ingested), or through a meta-physical infliction of psychosocial stress; multiple studies have deciphered how both these external factors may signal imbalance and subsequent reactionary mechanisms within the body—including, but not limited to, epigenetic modifiers. Once recorded in the body, these modifications have the capability to migrate through subsequent generations, transgenerationally (meaning, as far as great great grandchildren).

Michael Skinner is a highly cited contemporary biologist that fixates on the physical impressions of a material environment. For instance, his work on transgenerational inheritance of obesity from ancestral exposure to dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane—more commonly known as the notorious insecticide, DDT—suggests an existing nexus between pollutants and its temporal manifestation across non-exposed generations.34 While Skinner’s work is established within the epigenetics canon, he consistently disengages from sociological implications. Contested by the audience to consider colonial trauma as an abstract environment with similar transgenerational power, he responds weakly, deeming it a “tough sell.”35

It may not be easy to imagine how physical invaders could possibly trace themselves as biomarkers within the body, but in this era of globalised socio-political disequilibrium, it has become necessary to widen the notion of “environment” beyond the corporeal. Trauma, a catch-all term that embodies the psychological and physiological shock caused by social and/or physical threat; is a highly flammable variable that biologists have attempted to elucidate in a myriad of clinical studies, psychological diagnostics, and most recently, intergenerational manifestations. A 2014 study published in Nature Neuroscience reported altered microRNA expression, behavioural fear responses, and metabolic dysregulation in the nonexposed progeny of traumatised mice: all signals of epigenetic modification that transverse generations after an initial insult.36

Mark Wolynn, author of It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle, further compiles the latest research from leading experts in neuroscience and post-traumatic stress, elucidating how symptoms of psychological maladies could be shared within a “family body.”37 Straying away from the controlled rodent studies, Wolynn unpacks how global traumatic events such as national terrorism, famine, and war, could afflict unexposed grandchildren with compromised cortisol levels, clinical depression, and elevated rates of suicide, in comparison to the general population.3839 While it is exciting to finally recognize the cosmological bridge within modern medical terms, the redundancy in these studies is especially frustrating to a broader collective of women, Native people, and environmentalists who have sensed these connections without highly specified “proof.” The Anthropocentric tendency to only acknowledge the “environment” after its catastrophic erosion is yet another property of what we define here as planetary melancholia.

05 Anthropocentric Bias: Planetarity, Pain, and Human Exceptionalism

So far, we’ve addressed fragments of existing literature that attempt to elucidate an unspeakable violence as it manifests outside and within the body. But it is worth admitting that these language exercises are futile if we are to fully decenter the human experience, and reclaim a planetary relational system that prioritises the health of nonhuman entities equally. With the rapid growth of technological advancements in artificial intelligence, we are sold the idea that this synthetic hive mind serves as a posthumanist tool to generate solutions. But a reflection of our own biases, the algorithm continues to reveal the human exceptionalism in our tech.

As recently as 2023, reporter Linda Douina Rebeiz queried the AI image generator DALL-E 2 to generate images of her hometown in Dakar, Senegal.40 Producing images of “arid desert landscapes,” and “ruined buildings,” the potency of the Western gaze is undeniable. If existing AI models are already proving strong bias in image generation, it is beyond doubt that the highly anticipated knowledge production promised by this tech will also prove exclusionary. Before moving forward, it is necessary to denounce the technological pipe dream that prevents us from finding answers from what has always been, beyond the human all around us.41

06 The Privilege to Heal: Self-Care, Mourning, and Power

The discourse around self-care, particularly its commodification and the disparities it underscores in access and privilege, aligns closely with the broader themes of mourning and power. Tressie McMillan Cottom and Pooja Lakshmin42 have criticised these neoliberal tendencies, calling it the "goopification" of self-care, highlighting how mainstream wellness narratives often ignore underlying structural inequalities and perpetuate a sense of individual fault for systemic failures. While unapologetically extracting and co-opting indigenous traditions into a US-Euro-centric wellness industry—one that already benefits from decades of New Age-ism and Western hegemony over popular spiritual discourse. I mean– when was the last time you saw an Indian yoga teacher in the US? Cottom rightly critiques the influencer-driven wellness industry for distracting from "real urgent structural pain" that intersects with various forms of inequality. Lakshmin extends this critique, arguing for a version of self-care that involves deep, value-driven internal work, a “real self-care”,43 emphasising four key pillars: boundaries, self-compassion, values, and power.

[Faux self care] maintains the status quo in your relationships and in our broader social structures. [...] You can’t meditate your way out of a 40-hour work week with no childcare. Faux self-care keep us looking outward—comparing ourselves with others or striving for a certain type of perfection. Worse, it exonerates an oppressive social system that has betrayed women and minorities. [..]

Real self-care, in contrast, is an internal, self-reflective process that involves making difficult decisions in line with our values, and when we practice it, we shift our relationships, our workplaces, and even our broken systems. The result—having ownership over your own life— is nothing less than a personal and social revolution. [..]

So my thesis is that instead of thinking of self-care as taking 15 minutes out of your day to meditate or go for a walk, we need to be thinking about self-care as something that is threaded through every single decision you make in your life — the small decisions and the big decisions. So it’s not a task to check off of your list. It’s actually something to embody.

Relatedly, Tony Walter had this to say in his exploration of ‘complicated grief’:

Grief, like death itself, is undisciplined, risky, wild. That society seeks to discipline grief, as part of its policing of the border between life and death, is predictable, and it is equally predictable that modern society would medicalize grief as the means of policing how we express and process our emotions.44

Parallelly, Pittu Laungani shows us that the privilege to heal and mourn is intricately linked to social and cultural hierarchies, exemplified here by the complex interplay of caste, social status, and ritual in the Indian subcontinent.

The case study deals with a high-caste orthodox Hindu Brahmin who dies in the house of a sex worker from the lowest Hindu caste. His death creates an unprecedented set of problems, not only for his own family members but also for all the high-caste Hindus in the village that are traumatised by the event. The orthodoxy into which the villagers and the chief Brahmin priest are shackled prevents him from finding a solution that will enable them to perform the last funeral rites in accordance with Hindu scriptures.45

In this context, the mere validation that it is accurate to perceive the event as a loss and normalising the grief response can allow the griever to move through the loss response without the complications that may occur when the griever is bereft not only of the lost entity, but of validation, recognition, and normalisation of their grief.46 Arguably, existing mourning rituals have their own roles and power structures. Transitioning into a paradigm that allows everyone and everything to grieve requires a systemic deconstruction of those privileges—otherwise, what even is the point? Within western frameworks, self-care and healing are largely predicated on maintaining model citizen status and being able to participate in capitalism. For instance, disabled people aren’t really allowed to participate in western healing/self-care practices, given the ableist design of most New Age spirituality; rather they are expected to transform themselves into an acceptable entity or… to die.47

Whether we admit it or not, there exists a very palpable hierarchy between the trauma experienced in the world as well as the people experiencing it—the disproportionate reaction to ongoing conflicts in Ukraine and Palestine show us how current geopolitics have and continue to privilege White pain, visibly dismissing the historic trauma of people from the global majority and the more-than-human world.

Towards Planetary Vocabularies of Grief

Beyond merely naming the complex emotional landscape we navigate, our articulation of planetary melancholia offers a framework for understanding the collective emotional toll of the global polycrisis, bridging the gap between personal experiences of grief and the larger environmental and social injustices that define our times. It underscores the necessity for new grieving practices that acknowledge the interconnectedness of our challenges, urging us to move beyond traditional rituals to embrace those that reflect the complexity of the Anthropocene.

In recognizing the inadequacy of traditional grieving rituals to encapsulate the breadth of planetary loss, we must consider traditional alternatives to existing—as well as the creation of new—mourning rituals, objects, and symbols conducive to mutual thriving. Just as the right wing has effectively utilised symbols to unite and mobilise, there is a profound opportunity for those advocating for planetary health and justice to craft symbols that encapsulate our shared vulnerabilities and hopes. George Floyd inadvertently became such a symbol, as are the victims of genocide in Gaza. How about nobody dies the next time?

Moreover, the development of these planetary vocabularies invites us into a space where grief is not a solitary or static experience but a dynamic relational process that can catalyse collective empathy, action, and transformation. Creating new grieving rituals and symbols requires a deep engagement with the diverse tapestries of culture, belief, and experience that constitute our planetary community, and offers new avenues for fostering interspecies solidarity towards ensuring a just and equitable transition.

In the next article in the Notes on Trauma & Transition series, we expand on these vocabularies and offer a broad survey of indigenous, artistic, and policy-based interpretations of ritualization. The hope is that by embracing these new vocabularies, we may open ourselves to the possibility of not just finding meaning in our mourning, but also transforming our grief into a generative and actionable force for planetary healing and justice. Time will tell.

In fact, Eve Darian-Smith wrote a whole book about this before the General-Secretary made those comments. See: Darian-Smith, E. (2022). Global Burning: Rising Antidemocracy and the Climate Crisis. Stanford University Press.

Steffen, A. (2021, May 18). We’re not yet ready for what’s already happened. https://alexsteffen.substack.com/p/were-not-yet-ready-for-whats-already.

Bennett, W. L., & Livingston, S. (2018). The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication, 33(2), 122-139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323118760317.

Toffler, Alvin. (1970). Future Shock. New York: Random House.

Higgins K. (2016). Post-truth: a guide for the perplexed. Nature, 540(7631), 9. https://doi.org/10.1038/540009a.

Vargas Roncancio, I., Temper, L., et al. (2019). From the Anthropocene to Mutual Thriving: An Agenda for Higher Education in the Ecozoic. Sustainability, 11(12), 3312. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123312.

Pihkala P. Eco-Anxiety and Environmental Education. Sustainability. 2020; 12(23):10149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310149.

Barnwell, G., Stroud, L., & Watson, M. (2020). Critical reflections from South Africa: Using the power threat meaning framework to place climate-related distress in its socio-political context. Clinical Psychology Forum, 1(332), 7–15. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpscpf.2020.1.332.7.

Ray, S. J. (2021, March 21). Climate Anxiety Is an Overwhelmingly White Phenomenon. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-unbearable-whiteness-of-climate-anxiety.

Gen Dread. (2020, August 19). What’s wrong with the term “climate anxiety”? https://gendread.substack.com/p/whats-wrong-with-the-term-climate.

Bridle, J. (2019, June 19). Phenological Mismatch. e-flux Architecture. https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/becoming-digital/273079/phenological-mismatch.

Albrecht, G., et al. (2007). Solastalgia: the distress caused by environmental change. Australasian Psychiatry: Bulletin of Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, 15 Suppl 1, S95–S98. https://doi.org/10.1080/10398560701701288.

Sheldrake, M. (2023). Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds & Shape Our Futures. The Bodley Head.

Ekeroth, Z. (2024, January 16). Steadfastness and What We Can Learn From Mushrooms. BC Coop Association. https://bcca.coop/steadfastness-and-what-we-can-learn-from-mushrooms.

Defebaugh, W. (2022, July 15). Matter of Life and Death. Atmos. https://atmos.earth/fungi-mushrooms-life-and-death.

Boss, P. (1999). Ambiguous Loss: Learning to Live with Unresolved Grief. Harvard University Press.

See also: Tippett, K. (2021, November 8). Pauline Boss — Navigating Loss Without Closure. On Being with Krista Tippett. https://onbeing.org/programs/pauline-boss-navigating-loss-without-closure.

Jon Soske’s exploration of small worlds, large worlds, and systems unpredictability excellently expands on this. See: Soske, J. (n.d.). Small and Large Worlds. Polycene Design Manual. https://polycene.design/Small-and-Large-Worlds.

Johar, I. (2024, January 28). 7 Structural Shifts: Reconfiguring Transition Landscapes. Medium. https://provocations.darkmatterlabs.org/7-structural-shifts-25c5e0801b9b.

Silver, D., et al. (2011, September 3). Beyond PTSD: Soldiers have Injured Souls. Truthout. https://truthout.org/articles/beyond-ptsd-soldiers-have-injured-souls.

Zayyad, A. A. (2015, July 6). Israeli Soldiers Break Their Silence on the Gaza Conflict. Voices. https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/voices/israeli-soldiers-break-their-silence-gaza-conflict.

Gilroy, P. (2013). Postcolonial Melancholia (The Wellek Library Lectures). Columbia University Press.

Lieberman, S. (1979). A transgenerational theory. Journal of Family Therapy, 1(3), 347–360. https://doi.org/10.1046/j..1979.00506.x.

Menakem, R. (2017). My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies. Central Recovery Press.

Choi, A. S., & Lehrer, R. (2022, December 13). Episode Nine Transcript: The future with adrienne marie brown. Grief, Collected. https://www.griefcollected.com/transcripts/cwls1doc3trfjrng6qdbccki21byk9.

Morris, A. (2020, May 18). Children of the Climate Crisis. Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/children-climate-crisis-eco-anxiety-968673.

Schiffman, R. (2022, April 28). For Gen Z, Climate Change Is a Heavy Emotional Burden. Yale E360. https://e360.yale.edu/features/for-gen-z-climate-change-is-a-heavy-emotional-burden.

Zimmerman, R. (2023, June 14). Dinner parties and vulnerability: How a new generation has changed grief. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wellness/2023/06/14/grief-changing-generations.

Signorini, I. (1982). Patterns of Fright: Multiple Concepts of Susto in a Nahua-Ladino Community of the Sierra de Puebla (Mexico). Ethnology, 21(4), 313–323. https://doi.org/10.2307/3773762.

Ibid. 318.

The central dogma of molecular biology is a theory stating that genetic information flows only in one direction, from DNA, to RNA, to protein, or RNA directly to protein.

“Respecting the Principle of Biological Relativity” in Denis, Noble. Dance to the Tune of Life: Biological Relativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017. 232.

Navarrete, Valerie. (2023) "Migratory Material: Epigenetics & Weaving at the US-Mexico Border" Masters Theses. 1126. https://digitalcommons.risd.edu/masterstheses/1126

Waddington C.H. (1957). The Strategy of the Genes: a discussion of some aspects of theoretical biology. Allen & Unwin, London.

Skinner, M. K., et al. (2013). Ancestral dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) exposure promotes epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of obesity. BMC medicine, 11, 228. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-228.

Link to the lecture video tape,“Ancestral Ghosts in Your Genome: Epigenetic Transgenerational Inheritance.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b3IOUmT8YIE.

Gapp, K., Jawaid, A., Sarkies, P., Bohacek, J., Pelczar, P., Prados, J., Farinelli, L., Miska, E., & Mansuy, I. M. (2014). Implication of sperm RNAs in transgenerational inheritance of the effects of early trauma in mice. Nature neuroscience, 17(5), 667–669. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3695.

Chapter 2 in Wolynn, M. (2016). It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle. United Kingdom: Penguin Publishing Group.

Hughes V. (2014). Sperm RNA carries marks of trauma. Nature, 508(7496), 296–297. https://doi.org/10.1038/508296a.

Albert Bender (2015) “Suicide Sweeping Indian Country is Genocide,” People’s World. https://www.peoplesworld.org/article/suicide-sweeping-indian-country-is-genocide.

Small, Zachary (2023, July 4) “Black Artists Say A.I. Shows Bias, with Algorithms Erasing Their History.” The New York Times. www.nytimes.com/2023/07/04/arts/design/black-artists-bias-ai.html.

Dr. Emily Bender and Timnit Gebru are two leading voices on issues of AI ethics, most notably recognized for their seminal paper, “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” (2021). https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3442188.3445922.

Cottom, T., & Pooja Lakshmin. (2023, September 19). Transcript: Boundaries, Burnout and the ‘Goopification’ of Self-Care. The Ezra Klein Show. https://web.archive.org/web/20231116163654/https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/19/podcasts/transcript-tressie-cottom-interviews-pooja-lakshmin.html.

Real Self-Care. Pooja Lakshmin, MD. https://www.poojalakshmin.com/realselfcare.

Walter, T. (2006). What is Complicated Grief? A Social Constructionist Perspective. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 52(1), 71-79. https://doi.org/10.2190/3LX7-C0CL-MNWR-JKKQ.

Laungani, P. (2013). Religious rites and rituals in death and bereavement: An Indian experience. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education, 44(1), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/14635240.2006.10708058.

Walter, C. A., et al. (2009). Grief and Loss Across the Lifespan: A Biopsychosocial Perspective. United States: Springer Publishing Company.

We are indebted to scholar and artist Lilly Manycolors for challenging us to expand our framing in this piece.